I am presenting my research to date as part of the European Geosciences Union ‘General Assembly’, during the vPICO sessions on 28th April 2021. Part of session EOS7.4 | Exploring the Art-Science Interface | 09:00–12:30.

Category: Light

Encounter

As a practice-based research in the arts, it was inevitable that a project exploring ‘creative reflective practice’ as a key methodology, would shift emphasis throughout the research period. The role of encounter has become more productive to consider as I’ve gone through the research process.

There have been several generative encounters between me, Kielder Observatory and public audiences. These have included exchanges of art-science expertise, discussions on cultural perspectives of astronomy, and moments of reflection on artistic or organisational practice—whilst only a snapshot of activity, each exchange has potential for generating mutual benefit.

Engaging in encounter offers significant opportunities to develop new photographic provocations on dark skies for each partner. Through an imaginative voyage from Earth to outer space, enabled by artistic methods of production and creative reflective practice (in alignment with the objectives of KOAS), the work is attempting to create unconventional, artistic perspectives on astronomy. In Photography and Collaboration: From Conceptual Art to Crowdsourcing (2017), Daniel Palmer suggests that:

“Photographers are often most active whilst travelling in foreign places, which serves to reinforce the popular perception of photography as a existential act of wrangling with an alien world.” (Palmer, 2017, p. 2)

This is certainly true of my experience photographing at Kielder, where I have shot more film and digital files than I have during any previous project. Encountering the environment through the viewfinder (often alone, with no one else there), I have negotiated the place around me – the forest and the dark skies above. Using art to make sense of the sciences is nothing new – there are regular artist residencies at ESA and art-sci practice is a recurring interest for many creatives. The difference in my encounter is its focus on a local site of terrestrial Astro-tourism at Kielder, in all its transgressive off-grid-ness and welcoming cosmic community.

Alien worlds are curious and otherworldly. But sometimes (as living through the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us) the local can be just as extraordinary. Just as much as Kielder is a new, unexplored place to encounter for me, my curiosity and process as a artist is likely a strange thing to those outside of the creative sector. To move forward within our own fields of expertise, it is important to transcend the disciplinary confines of our familiar territory, to generate new expertise and knowledge perspectives.

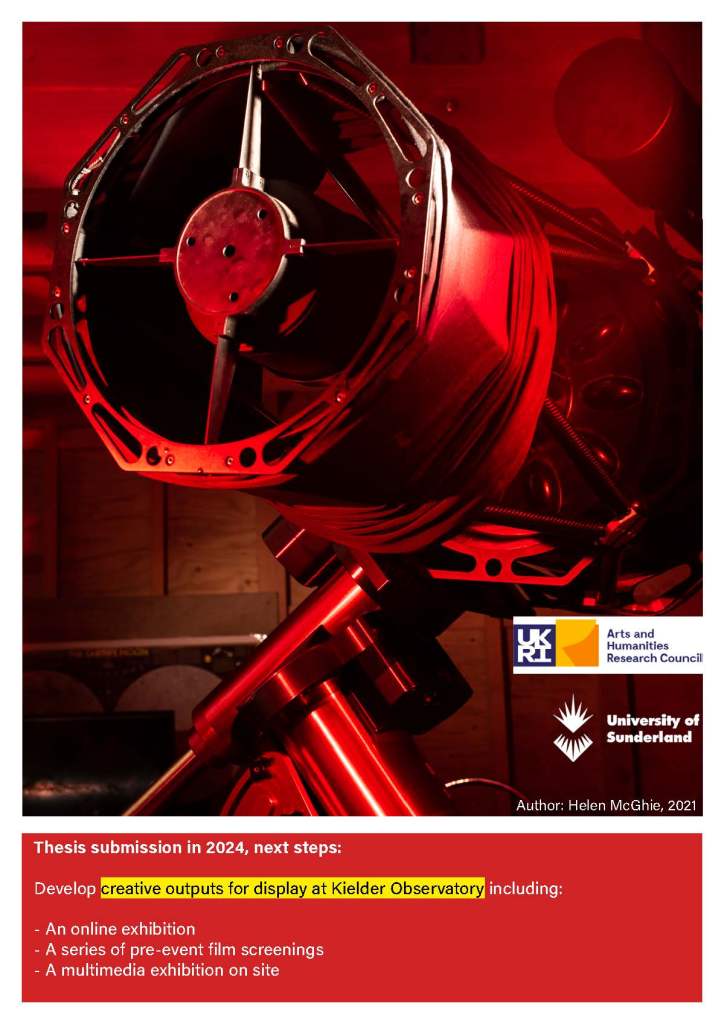

KOAS – a film in progress

_COSMIC WEBS_ENCOUNTER_NIGHT_OBSERVATION_ SITUATEDNESS_

PHOTOGRAPHIC_UNIVERSE_MECHANICAL_PERSPECTIVE_FOREST_TIME_SPACE_KNOWLEDGE_ENVIRONMENT_LOOP_PAST/PRESENT/FUTURE_VISION_SPACE-TIME_GAP_

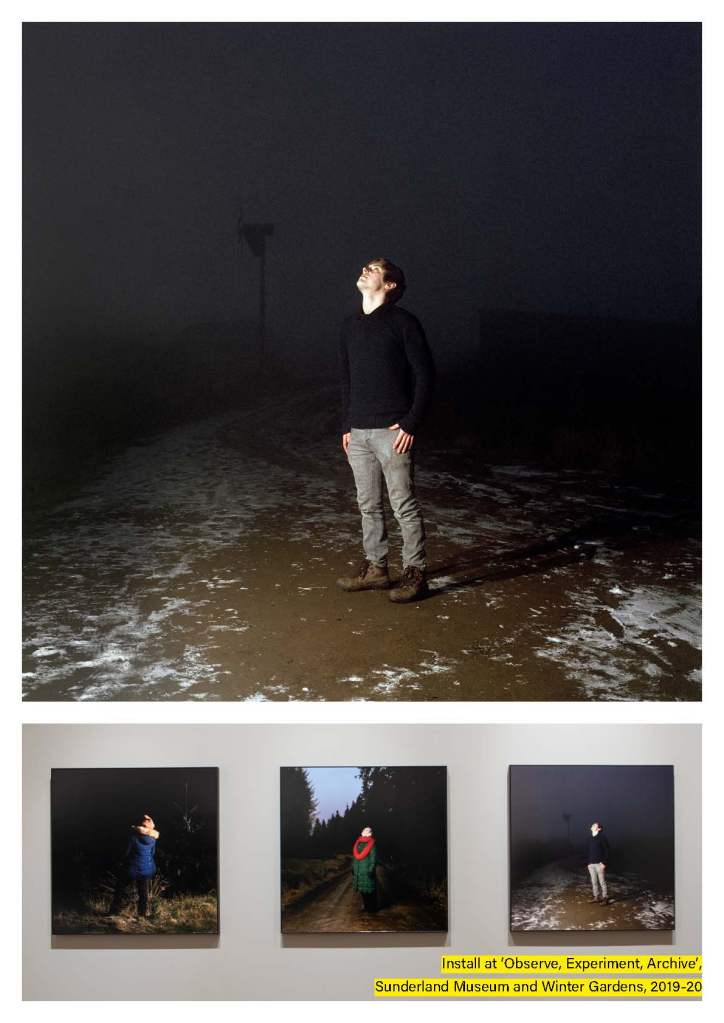

‘Observe, Experiment, Archive’ #1 (Dark Adaptation)

A group photography exhibition at Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens. Exhibiting artists: Mandy Barker, Tessa Bunney, Liza Dracup, Sophie Ingleby, Helen McGhie, Maria McKinney, Robert Zhao Renhui and Penelope Umbrico.

From 15th November 2019 – 5th January 2020, my photography was exhibited as part of the exhibition ‘Observe, Experiment, Archive’ at Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens, programmed and curated by the North East Photography Network (NEPN) which explored:

“[…] the parallels between photography and scientific methods such as observation, experimentation and archiving [and] how contemporary photographic artists can respond to both scientific innovation and historical collections, their work transforming our world through light and lens” (Sunderland Culture, 2019)

This was an opportunity to develop and produce work for the context of a public museum, where an appropriate engagement for the audience (families, schools, individuals not specialised in astronomy) was crucial.

Using Kielder Observatory (located in Europe’s largest International Dark Sky Park) as the context for creating photography, my practice-led PhD is centred around the cultural connectedness of astronomy and photography with an emphasis on the personal experiences had by the night-sky observer in northern England – the research is underpinned by the work instigated in Donna Haraway’s theory of Situated Knowledges which challenged the epistemological viewpoints in contemporary technoscience practice. Since reflecting on my theoretical and methodological position during my recent Annual Monitoring Review, my project design has become much clearer than it was when I embarked on the research in 2017.

Many cultural images of dark skies are records of observations had captured and shared through photography (of course, images can be digital fabrications built by algorithms and AI, but this is not the focus of my PhD) – there is often little or no trace of the observer in astrophotography, no evidence of a transformative experience had, the physicality of the local temperature/altitude or the journey/astronomical pilgrimage made prior to arrival. The aesthetic conventions of dark sky imaging involve applying ‘false colour’ and high saturation to dense stars, to render non-visible light visible (Ventura, 2013). Government-funded organisations (each with its own agenda on national security) such as NASA and the ESA (as well as astronomers at the Hubble Heritage Project) have set the visual standards for how the public recognises outer space, by creating ‘copyright free’ images available for download on official sites (perhaps set up to create a rationale for the allocation of public taxes?); with access to such data-rich resources, amateur astrophotographers have ongoing stylistic inspiration for the design of their own images and continue to uphold the aesthetic style set. As the case with all genres of photography, these images are anthropocentric representations of the real, mediated through the mechanics of photography (with long exposures making invisible rays of light visible to the human eye) and do not represent an entirely accurate visualisation of moments witnessed. To consider this, I wonder if it is possible to visualise a closer experience of dark sky observation in northeast England? And can the creation and dissemination of the photographic art that I make enhance the cultural offer of Kielder Observatory, as a remotely located public-outreach astronomical facility in Northumberland?

In Observe, Experiment, Archive, my large-scale photograph ‘Dark Adaptation’ (2019) presented the audience with a red, rocky landscape – a nocturnal car park captured under the glow of artificial red light. To the photographer working with analogue processes or to those familiar with televised crime scene dramas, this hue might be reminiscent of the ruby glow of the black and white darkroom, the stable conditions required for one to develop images under light-sensitive conditions. To an astronomer, red light maintains the nocturnal conditions for sensitised visibility to the stars, for viewing a glimpse of white light (from the glow of a smartphone or beam emitting from car headlights) immediately blinds night vision, the ability to see the dullest ancient starlight for around 30 minutes.

By photographically capturing the dark environment with a wash of scarlet-lit ground in ‘Skyspace car park’ (where guests eagerly await the night’s activities at Kielder Observatory) and then printing it as an almost life-size scene for exhibition, the landscape has been transported from a topological reality to a theatrical representation. Through the exhibition, the visitor’s gaze becomes confronted a night-time Martian landscape, after the fact of when it was captured, a life-size record of a place conquered by the camera, not unlike the pictorial records captured by the human-operated rover cameras that meticulously roam the red planet. Printed for Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens (a cultural site built to inspire the regional audiences who visit), Dark Adaptation becomes a Martian museum diorama, similar to ‘Mission to Mars’ at the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, which contains a 1:2 scale model of the Viking Lander, a machine that studied the planet’s surface from 1976. Through the installation of artificial light and props, the blank canvas of a theatre stage becomes an elaborate ‘elsewhere’ and the application of artificial lighting on to the surface of a car park in Dark Adaptation performs a similar function. The relationship between a vehicle and its driver has been reflected on by sociologist John Urry:

“Dwelling at speed, car-drivers lose the ability to perceive local detail, to talk to strangers, to learn of local ways of life, to stop and sense each different place. […] The environment beyond that windscreen is an alien other” (Urry, 2006, p. 23)

Kielder Observatory is located in a remote part of Northumberland, only accessed by vehicle; for new visitors unfamiliar with Kielder Forest, driving along the winding, dark roads towards the observatory may be a nerve-racking experience, made worse by the security of mobile phone signal that weakens to non-existence. Whilst a vehicle provides security for passengers for the duration of a trip, on arrival, they step outside of a familiar automotive interior and conquer a new frontier: Urry’s ‘alien other’.

I am reminded of Luci Eldrige’s PhD Mars, Invisible Vision and the Virtual Landscape: Immersive Encounters with Contemporary Rover Images, exploring viewing apparatuses and the transformative possibility of the ‘glitch’ as a way to cut through the imaging spectacle, using the Mars Yard (European Space Agency’s Martian research terrain) as one example; filled with sandy ground and pasted with the theatrical backdrop of rover imagery, the glitch arises when the illusion of this otherworldly land is momentarily broken through a recognition of the manmade flaws in its construction. Dark Adaptation does not fill the entire room, there is no rocky ground for visitors to immersively step upon and the edge of the image is clearly hung upon a grey museum wall – the work presents itself as an educational spectacle to inspire and imbue curiosity for the audience, contained within itself, the image illustrates an anthropocentric accomplishment of another world that humans may one day inhabit.

References:

Eldridge, L. (2017) ‘Mars, Invisible Vision and the Virtual Landscape: Immersive Encounters with Contemporary Rover Images’, PhD Thesis, Royal College of Art.

Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14(3), p. 575.

Hello Universe (2019-20) [Exhibition]. National Science and Media Museum, Bradford. 19 July 2019 – 22 January 2020.

Observe Experiment Archive (2019-20) [Exhibition]. Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens, Sunderland. 15 November 2019 – 5 January 2020.

Urry, J. (2006) ‘Inhabiting the Car’, The Sociological Review, 54(1_suppl), pp. 17–31.

Ventura, A. (2013) ‘Pretty Pictures: The Use of False Color in Image of Deep Space’,Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Studies, (19).

KOAS Staff Portraits – #4

Shoot: 19th January 2019

Location: Kielder Forest

John Hilliard – ‘Black Depths’

The Depths of Space / The Depths of the Pool /

The Depths of the Fire / The Depths of the Earth

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hilliard-black-depths-t14511

Image: TATE

Transgressive Light

Shoot: 23rd February 2019

Location: Kielder Forest

Esther Teichmann and darkness

“Bathed in the silent darkness of night, half-light of red liquid, we see differently here–half blinded, there is clarity within the inverted, hovering projection, within the floating shivering movement of image appearing upon its material support.” (2011, p. 82)

Reference:

Teichmann, E. (2011) Falling Into Photography: On Loss, Desire and the Photographic,PhD Thesis, Royal College of Art. Available at: http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1173/1/Esther_Teichmann_PHD_RCA.pdf(Accessed: 10 September 2018).

Space Blankets and False Colour

“To acknowledge the human-made aspects of the deep space picture, the inevitable acts of individual conjecture and mediation involved in its creation, is thus to acknowledge the limits of human knowledge and perception.” (2013)

Photographic representations of starry skies evoke the imagination, but I wonder if there are alternate creative methods involving experiences of dark, immersive spaces where an audience might experience astronomy differently? Above are initial studio tests: I experimented with space blankets, the female form, flash lighting and colour gels. The saturated colour relates to the ‘false colour’ used in many Astrophotography images, the ‘space blanket’ his a lightweight material that coats exterior surfaces of spacecraft.

Reference:

Ventura, A. (2013) ‘Pretty Pictures: The Use of False Color in Images of Deep Space’, InVisible Culture 19 (Fall).

‘Picturing the Cosmos: Hubble Space Telescope Images and the Astronomical Sublime’, Elizabeth A. Kessler.

The chapter ‘Translating Date into Pretty Pictures’ dissects the way ‘Astrophotography’ is ‘made’ from data, where data from ‘flexible image transport files’ (FITS) are downloaded from the Hubble Telescope before inputted into imaging programs such as ‘IRAF’ software or more recently via the ‘FITS Liberator’ plugin for Adobe Photoshop. Astrophotographers then work through a series of processes to render this data and ‘make visible’ areas of the data which lie beyond the electomagnetic spectrum.

-

-

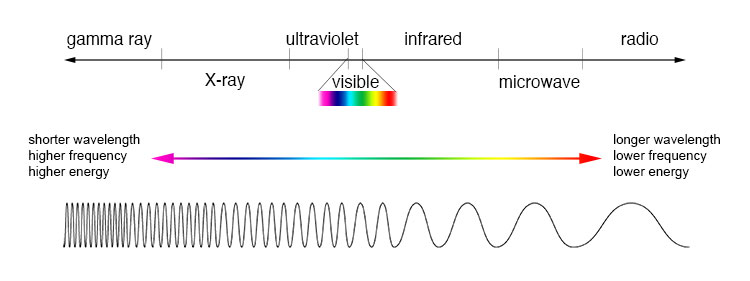

The Electromagnetic Spectrum. Ultraviolet or Infrared light may be collected as data by the Hubble Telescope, but this is invisible to the human eye.

These processes include:

Building Composites – stitching together multiple exposures that have been photographed with different filters.

Selecting Contrast – ‘revealing’ structures of the unseen such as nebula/gas clouds (some Astrophysicist’s match each pixel to lumen/light intensity data and have a closer association with nature)

Determining Colour – this isn’t scientifically assigned, although blue often characterises the least energy and red the most energy. Kessler repeatedly states that some astrophotography aesthetics are decided by ‘trained judgement’ or through a set of pre-determined algorithms associated with a particular institution.

Kessler cites: “It’s important to use a different color for each data set. Otherwise, distinct information from each of the data sets is lost.” (Rector et al., “Image-Processing Techniques for the Creation of Presentation-Quality Astronomical Images,” p. 609)

Cosmetics – known as ‘Cosmetic Cleaning’, where cloning within Adobe Photoshop removing stray cosmic rays and difference in background colour from composite blending. Interestingly, ‘diffraction spikes’ (rays of light caused by telescope optics) are often kept, or even added into images where they don’t exist, they appeal to the aesthetic contemplation of ‘starry skies’.

“Perception and representation, number and image, index and symbol–the hybridity of the Hubble images raises a question that haunts all scientific images: What is their relationship to the phenomena they purport to represent?” (2012, p. 128)

- Screenshot from The Hubble Heritage Project’s website.

Kessler makes useful links to existing philosopher and critical thinkers:

- David Batchelor, Chromophobia. London:Reaktion Books, 2000

- Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator” and The Arcades Project, p476 ‘

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement. 1790.

- Ansel Adams, The Negative (describes physical changes in photography: dodging and burning etc.)

- William Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, 1992. “[…] an interlude of false innocence has passed. Today, as we enter the post-photographic era, we must face once again the ineradicable fragility of our ontological distinctions between the imaginary and the real, and the tragic elusiveness of the Cartesian dream. We have indeed learned to fix shadows, but not to secure their meanings or to stabilize their truth values; they still flicker on the walls of Plato’s cave.” (p. 225)

- Time Magazine, October 25, 1989, “150 Years of Photojournalism”. A modified image of Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon shows all seven astronauts, carrying the caption “A picture of something that never took place”.

- Bruno Latour “reversible chain of transformations” – a series of changes that link messy phenomena in the world to a representation. (Latour, Pandora’s Hope, p71)

Reference:

Kessler, E. A. (2012) Picturing the Cosmos: Hubble Space Telescope Images and the Astronomical Sublime. Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press.